Start Here

Regulations and Policies

The Regulations and Policies module is a cornerstone of the Basic Qualification curriculum, providing learners with a detailed understanding of the legal and operational framework for amateur radio in Canada. This module covers all aspects of regulatory compliance, from obtaining and maintaining your amateur radio authorization to understanding international privileges and ITU regulations. It explains the rules for station identification, operational standards, and the restrictions on content and equipment use, ensuring learners understand the boundaries and responsibilities of their operating privileges.

Key topics include authorization requirements, eligibility criteria, terms and conditions of operation, and procedures for managing interference and emergency communications. Learners also explore the technical standards for frequency allocations, power restrictions, and RF safety, as well as the process for resolving disputes and managing antenna structure approvals. Additionally, the course delves into the unique aspects of international operation, such as reciprocal privileges and coordination with foreign operators, offering a global perspective on amateur radio practice.

Be sure to login to your hamshack.ca account to track your progress by clicking the [Mark Complete] Button at the bottom of each lesson. You can contact VE7DXE to sign-up for the new Basic Amateur course.

B-001-001 – Radio Licences, Applicability, Eligibility of Licence Holder

Amateur radio in Canada doesn’t operate in a vacuum. It exists within a well-established legal structure that defines who can participate, what privileges they have, and how radio stations must be managed. Before touching a microphone or key, every amateur must understand where the authority for amateur radio comes from, who enforces the rules, and what documents define the service itself. These foundational principles are the starting point for every new operator.

❓ What gives amateur radio its legal foundation in Canada?

Before anyone in Canada can legally transmit on the amateur bands, they must be authorized—and that athourization authority must come from somewhere. Amateur radio exists within a well-defined legal framework, ensuring that operators follow national guidelines for equipment use, frequency access, and communication practices. These rules also help protect the amateur spectrum from both intentional and accidental interference.

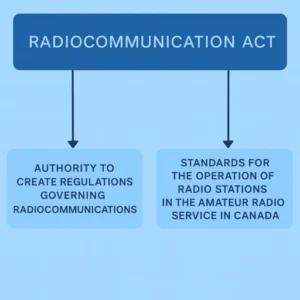

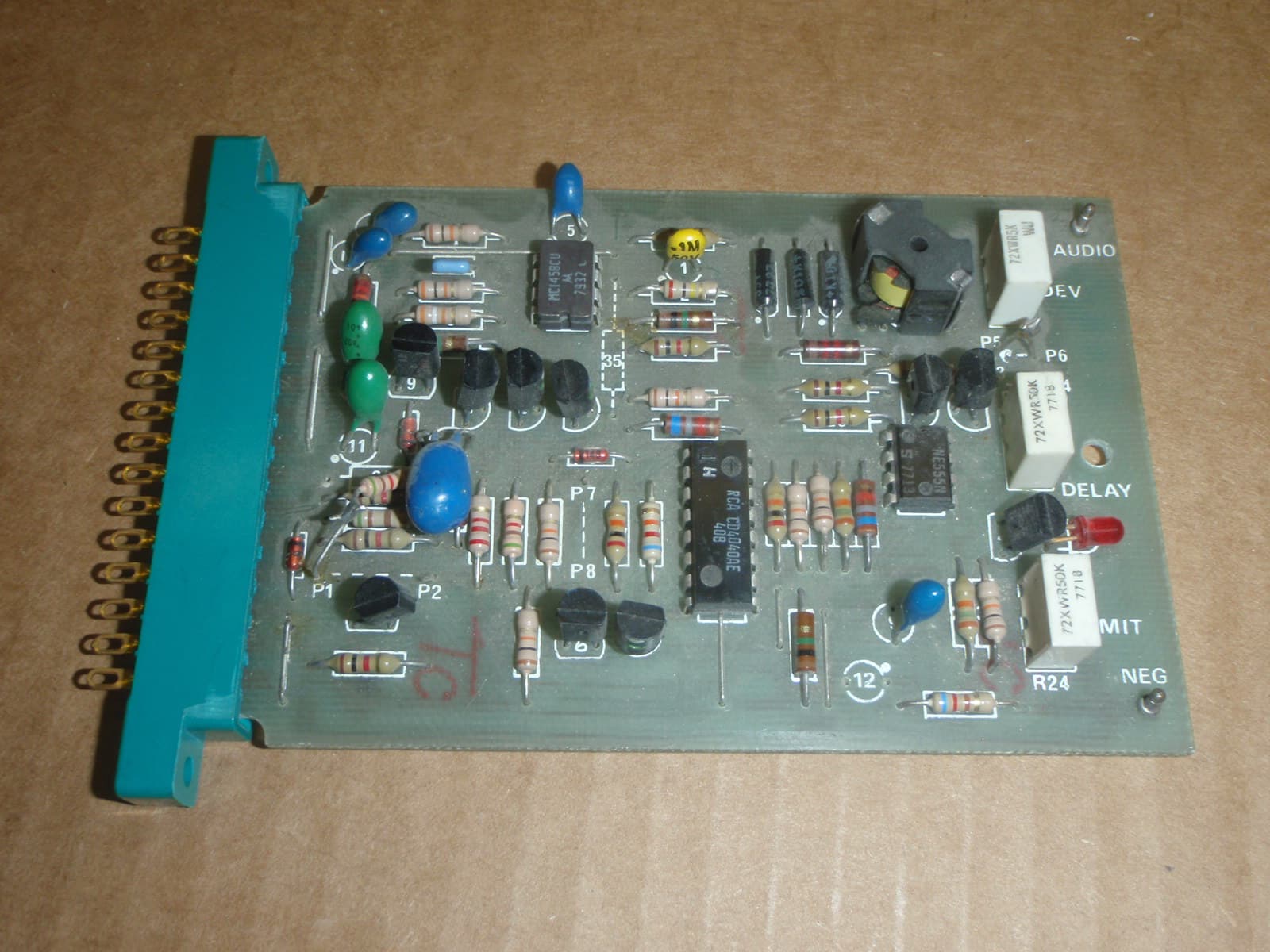

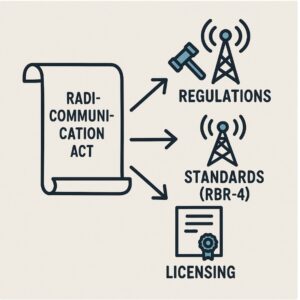

At the heart of this framework is the Radiocommunication Act. This Act gives the Canadian government the authority to create and enforce regulations that govern radio operations. It is the document that underpins everything from licensing to technical standards. For example, the Radiocommunication Act specifically assigns the power to create regulations governing radiocommunications, including the amateur service. It also authorizes the

publication of technical standards such as the RBR-4 Standards for the Operation of Radio Stations in the Amateur Radio Service in Canada. Without this legislative foundation, there would be no formal standards for amateur radio to operate within Canadian law.

B-001-001-001, B-001-001-002

🏛️ Who manages the rules once they are created?

🏛️ Who manages the rules once they are created?

Once the Radiocommunication Act defines the rules, someone needs to administer and enforce them. That job belongs to Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada—often referred to as ISED. This federal department handles the day-to-day management of spectrum access across the country, including amateur radio, commercial broadcasting, cellular, and more.

For hams, ISED is the department that issues operator certificates, investigates interference complaints, and sets national policies on spectrum allocation. When you apply for a callsign or have technical questions about your station’s compliance, you’re working within ISED’s jurisdiction.

B-001-001-003

📖 What defines amateur radio in Canada?

While the Radiocommunication Act lays the groundwork, the detailed rules that define the amateur radio service are found in the Radiocommunication Regulations. These regulations specify what amateur radio is, who qualifies, what privileges they get, and what limitations apply. They’re the practical guidebook that turns legal authority into operating reality.

The Radiocommunication Regulations outline expectations for operator conduct, station identification, power limits, and frequency usage. They ensure the service remains non-commercial and focused on technical learning, experimentation, and emergency support. This document plays a key role in preserving the spirit of amateur radio while also ensuring consistent national standards.

B-001-001-004

🔍 B-001-001 Lesson Summary

| Concept | What It Means | Formula / Term | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Legal Foundation | Amateur radio in Canada exists because federal law authorizes it through the Radiocommunication Act. | Radiocommunication Act | Creates the legal right to operate and ensures radio rules are applied consistently nationwide. |

| Regulatory Authority | The federal department ISED ( Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada ) manages the amateur service. | ISED | Oversees licensing, callsigns, and interference issues to keep the spectrum organized and fair for all users. |

| Operating Rules | The Radiocommunication Regulations outline who may operate and how stations must be run safely and responsibly. | Radiocommunication Regulations | Define operator conduct, station identification, and technical limits to keep the hobby safe and non-commercial. |

| Technical Standards | The RBR-4 Standards document sets the technical requirements for equipment and operation. | RBR-4 Standards | Ensures stations meet consistent performance levels and minimize interference across Canada. |

| Purpose of Amateur Radio | Amateur radio is a non-commercial service for learning, experimentation, and public service. | Non-Commercial Service | Supports education and community communication while preserving the spirit of self-training and public benefit. |

📋 Lesson Practice Exam ▼

B-001-002 – Licence Fee, Term, Posting Requirements, Change of Address

Changes in address, lost certificates, or even call sign upgrades are part of every ham’s journey and understanding the requirements around fees, certificate validity, and address changes ensures that you stay compliant with federal regulations and avoid penalties or lapses in your operating privileges.

This section focuses on the core responsibilities every amateur operator in Canada must know about their certificate: how long it’s valid, where it should be stored, and what to do when you move.

📨 What should you do when your address changes?

When you move, your Amateur Radio Operator Certificate doesn’t automatically update. You are required to Inform Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada of your new mailing address. This must be done within 30 days of the change. Not doing so can result in administrative complications or delays in important notices from ISED.

Remember, you must notify Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada within 30 days of a change of mailing address. This ensures your contact information stays current in the national licensing system and that your certificate remains valid.

B-001-002-001, B-001-002-003

🪪 How long does your certificate last—and where should it be kept?

In amateur radio, passing the Basic exam isn’t just a milestone—it’s a lifetime achievement. Once you’ve earned it, your Amateur Radio Operator Certificate is valid forever. It doesn’t expire, and there’s no need to renew it. The qualification is yours for life, a permanent recognition of your status as a licensed Canadian amateur radio operator.

But with that privilege comes an important responsibility: the certificate must be accessible when needed. According to the regulations, it must be retained at the station. This means it must be physically present and available where the station is located. If a radio inspector asks to see your Amateur Radio Operator Certificate, or a copy thereof, you are legally required to produce it within 48 hours. Keeping your certificate handy isn’t just good practice—it’s part of staying compliant.

B-001-002-002, B-001-002-004, B-001-002-005

🏠 Where should your certificate be kept when you’re not operating?

Many hams assume that if they’re not currently on the air or don’t have a home station set up, the location of their certificate doesn’t matter. But the regulations are clear: it must be retained at the address provided to Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada. This helps ensure consistency in enforcement and clarity if there’s ever an audit or investigation related to your callsign.

Having your certificate at the address you provided helps you demonstrate compliance, especially during times when you’re not actively operating but remain a licensed amateur.

B-001-002-007

💰 Are there fees for issuing or changing your certificate?

There’s good news for new operators: the initial cost to become licensed is Free. Likewise, if you move to another province or territory and request a new call sign prefix to reflect your location, that update is also Free.

However, if you want to change your current call sign voluntarily—such as upgrading to a two-letter suffix—there is a fee. That cost is 60 dollars.

B-001-002-006, B-001-002-008, B-001-002-009

🔍 B-001-002 Lesson Summary

| Concept | What It Means | Formula / Term | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Change of Address | You must inform ISED within 30 days whenever your mailing address changes. | 30-Day Notification Rule | Keeps your licence record current and ensures you receive all official correspondence from the regulator. |

| Certificate Validity | Your Amateur Radio Operator Certificate never expires once earned. | Lifetime Licence | Confirms your ongoing qualification as an amateur operator without renewals or additional fees. |

| Certificate Location | The certificate must be retained at the station or at your registered address. | Posting Requirement | Ensures the document can be shown to an inspector within 48 hours and verifies station compliance. |

| When Not Operating | Even if you’re off the air, the certificate should stay at the address on record with ISED. | Registered Address Rule | Maintains traceability of your licence and simplifies future audits or correspondence. |

| Licence Fees | There’s no fee for your initial certificate or for updating an address or prefix. Voluntary call-sign changes cost $60. | Fee Schedule | Clarifies which administrative changes are free and which incur a cost, helping you plan updates responsibly. |

📋 Lesson Practice Exam ▼

📘 B-001-003 – Licence Suspension or Revocation, Powers of Radio Inspectors, Offences and Punishments

Operating in the amateur radio service comes with privilege—but also responsibility. These responsibilities aren’t just moral or technical, they’re legal. Canada’s Radiocommunication Act and associated regulations set clear boundaries, enforce penalties, and empower inspectors to investigate violations. Understanding where those lines are is important to maintaining your certificate and protecting the amateur bands.

In this lesson, we’ll look at what kinds of actions can get an amateur operator into trouble, from out-of-band transmissions and false distress signals to interfering with legitimate communications. We’ll also explore the powers of ISED and radio inspectors—what they can do, and where their authority stops.

🚫 What happens if you transmit outside the amateur bands?

Each amateur operator in Canada is authorized to transmit only on frequencies allocated to the amateur service. Going beyond these limits—either intentionally or accidentally—can create interference to sensitive services like aviation, marine safety, or emergency communications.

To prevent this, transmissions outside amateur bands are prohibited and penalties could be assessed to the control operator. It’s the control operator’s legal duty to ensure their equipment is operating within assigned boundaries.

B-001-003-001

🆘 What are the consequences of faking an emergency?

Emergency phrases like “MAYDAY” carry life-and-death weight. Using them without a genuine emergency isn’t just irresponsible—it’s illegal. If an operator falsely transmits the word “MAYDAY,” it’s considered A false or fraudulent message under Canadian regulations.

Transmitting false information is never permitted, and potentially risks diverting emergency services, delaying aid to real victims, or interfering with emergency or commercial stations.

B-001-003-002, B-001-003-007

⚖️ What penalties could you face for serious violations?

Some offences—like false distress signals or intentional interference—go beyond technical violations. These are criminal matters under the Radiocommunication Act, and they carry serious penalties. If found guilty of either, the offender may be sentenced to A fine, not exceeding $5 000, or a prison term not exceeding one year, or both.

This penalty applies whether the violation was a prank, an act of defiance, or simply reckless behavior. Even if no harm was intended, to interfere with, or obstruct any radio communication, without lawful cause is considered unlawful and is taken seriously under federal law.

B-001-003-003, B-001-003-008

📜 Where are these rules written down?

All offences, penalties, enforcement powers, and legal definitions related to amateur radio in Canada are laid out in the The Radiocommunication Act. This law authorizes ISED to issue, suspend, or revoke certificates, defines illegal transmissions, and establishes penalties.

Every operator should be familiar with the contents of the Act, as it serves as the legal foundation for amateur radio—it’s the rulebook that protects the shared amateur radio spectrum from misuse.

B-001-003-004

🛑 Can inspectors or the Minister act without due process?

Inspectors and the Minister of Innovation, Science and Industry have the authority to enforce regulations—but that authority has boundaries. For example, it’s not correct to assume A radio inspector may enter a dwelling without the consent of the occupant and without a warrant. Canadian law protects the privacy of your home, even during investigations.

Similarly, the Minister may suspend an Amateur Radio Operator Certificate for cause, but this never occurs with no notice, or opportunity to make representations thereto. Due process is built into the enforcement process, ensuring fairness and accountability.

B-001-003-005, B-001-003-006

🔍 B-001-003 Lesson Summary

| Concept | What It Means | Formula / Term | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transmitting Outside Amateur Bands | Operators may only use frequencies assigned to the amateur service. Transmissions beyond these limits can interfere with protected services. | Band Compliance | Staying within authorized bands prevents interference with aviation, marine, and emergency systems and protects the operator’s licence. |

| False Emergency Calls | Using distress signals such as “MAYDAY” without a real emergency is illegal and considered a fraudulent message. | False or Fraudulent Transmission | Misuse of emergency signals diverts responders and is treated as a serious offence under federal law. |

| Penalties for Violations | Deliberate interference or fraudulent transmissions can result in fines up to $5,000, imprisonment for up to one year, or both. | Criminal Penalty | Highlights the legal seriousness of misuse and reinforces personal responsibility for lawful operation. |

| Legal Source of Authority | All offences, penalties, and enforcement powers are detailed in the Radiocommunication Act, which governs amateur radio in Canada. | Radiocommunication Act | Provides the legal framework protecting the spectrum and ensuring fair enforcement across all radio services. |

| Inspector and Ministerial Powers | Inspectors cannot enter a private dwelling without consent and a warrant. The Minister may suspend or revoke a certificate only with notice and opportunity to respond. | Due Process | Guarantees fairness and privacy while maintaining the government’s ability to enforce radio regulations responsibly. |

📋 Lesson Practice Exam ▼

B-001-004 – Operator Certificates, Applicability, Eligibility, Equivalents, and Recognition

Becoming a certified amateur radio operator in Canada isn’t just about passing an exam—it’s about understanding how qualifications work, what legal criteria apply, and how certifications from other services or countries might translate. This lesson breaks down the pathway to your first certificate, what qualifications unlock additional privileges, and how special cases like maritime certification or Morse code fit into the bigger picture.

You’ll also learn the important requirements every candidate must meet to earn their certificate and what it means to hold an Advanced qualification.

🎓 Who can get certified as a ham operator in Canada?

One of the great things about amateur radio is that There are no age limits for being granted an Amateur Radio Operator Certificate with Basic Qualification.

However, all candidates must Have a valid address in Canada. This ensures that operators can be properly licensed, reached for updates, and held accountable under Canadian regulations. As long as you’re located in Canada, you’re eligible to be certified!

B-001-004-001, B-001-004-007

📝 What do you need to pass to get your certificate?

Before you can receive your certificate, you must pass the standard written exam covering operating practices, regulations, and basic electronics. This is known as the Basic Qualification. It’s the foundation for all further privileges in amateur radio.

Additionally, if you already hold another recognized certificate—like the Canadian Radiocommunication Operator General Certificate Maritime (RGMC)—you may also be issued an Amateur Radio Operator Certificate without retaking the Basic exam. This recognition of equivalent training helps professionals from other radio services transition into amateur radio more easily.

B-001-004-002, B-001-004-003

🔁 How are additional qualifications earned?

Once you’ve earned your Basic Qualification, you’re free to explore further privileges through Advanced or Morse qualifications. These additional qualifications can be obtained in any order. You might choose to pursue your Morse Qualification first, or go straight into the Advanced exam.

B-001-004-004

✉️ What’s required for the Morse code endorsement?

Although Morse code is no longer required to obtain HF privileges. for most privileges, it’s still offered as an optional endorsement for those interested in CW (continuous wave) operation. To qualify, you must demonstrate both sending and receiving skills at a speed of 5 wpm (words per minute).

This relatively low threshold means that almost anyone can learn Morse with a bit of practice. In Canada, Morse code is no longer required to access HF bands (below 30 MHz). Instead, operators have two ways to qualify for HF privileges:

- Score 80% or higher on the Basic Qualification exam, or

- Pass the Advanced exam (or hold the older Morse code qualification)

This change, made in 2005, modernized access rules while still ensuring operators have a strong grasp of radio fundamentals before using the HF bands.

B-001-004-005

🚫 What does the Advanced Certificate not allow?

The Advanced Qualification unlocks powerful new privileges within the amateur radio service, including homebrewing transmitters, higher power levels, and operating repeaters. But that authorization applies to amateur service only.

If you’re wondering whether it lets you operate in other services—like aviation, marine, or commercial—the answer is simple: No other service. Holding an Advanced Amateur Radio Operator Certificate gives you extra rights in the amateur bands, but nothing beyond them.

B-001-004-006

🔍 B-001-004 Lesson Summary

| Concept | What It Means | Formula / Term | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eligibility for Certification | Anyone with a valid Canadian mailing address may be granted an Amateur Radio Operator Certificate. There are no age limits. | Canadian Address Requirement | Ensures operators can be contacted and held accountable under Canadian regulations. |

| Basic Qualification | Applicants must pass a written exam covering regulations, operating practices, and electronics fundamentals to earn the Basic Qualification. | Basic Exam | Serves as the foundation for all amateur privileges and is required before transmitting on any amateur frequency. |

| Recognition of Equivalents | Holders of certain recognized certificates, such as the Radiocommunication Operator General Certificate Maritime (RGMC), may receive an Amateur Radio Certificate without retaking the Basic exam. | Certificate Equivalency | Allows qualified radio professionals to transition easily into the amateur service. |

| Additional Qualifications | After earning Basic, operators may add Advanced or Morse endorsements in any order to expand their privileges. | Advanced / Morse Options | Encourages skill growth and access to higher power and additional modes as knowledge increases. |

| Morse Code Endorsement | A separate optional qualification requiring sending and receiving Morse at 5 words per minute. Not required for HF access since 2005. | 5 WPM Requirement | Honors traditional operating skills while keeping modern licensing flexible and inclusive. |

| Advanced Certificate Limitations | The Advanced Qualification grants more power and technical privileges but does not permit operation in any non-amateur service. | Amateur Service Scope | Clarifies that even advanced privileges apply only within the amateur bands and services. |

📋 Lesson Practice Exam ▼

📘 B-001-005 – Operation, Repair and Maintenance of Radio Apparatus on Behalf of Other Persons

In amateur radio, operators often collaborate, assist with station setup, or lend a hand in troubleshooting someone else’s gear. But there are limits to what you’re allowed to do on behalf of another person—even if you both hold certificates. This section explores when you can legally help, install, program, or repair equipment that doesn’t belong to you.

You’ll learn who must be certified, what kind of authorization is needed, and where regulatory lines are drawn. Understanding these conditions will help you avoid unintentionally violating licensing privileges.

🔧 Can you work on someone else’s equipment?

If you hold an Advanced Qualification, you’re permitted to build, repair, or modify amateur radio equipment—but only on behalf of another person who is authorized to operate it. In other words, you may do so if the other person holds an authorization for this apparatus. This ensures that all equipment remains tied to a licensed operator and is used within the bounds of amateur radio regulations.

The same rule applies to specialized modifications, like converting a land mobile transmitter for amateur use. Even if you have the technical skills, you can perform this work only if the other person holds an Amateur Radio Operator Certificate. These rules uphold accountability by preventing unauthorized modifications for unlicensed individuals.

B-001-005-001, B-001-005-002

🛠️ What must be true to install, repair, or place a transmitter in service?

Working on someone else’s amateur radio station—whether installing a new unit, running cables, tuning output, or placing a transmitter into service—means you must follow specific rules. Even with an Advanced Qualification, you’re not allowed to perform work that would let another person operate equipment beyond their certified privileges. The equipment must remain within the legal limits of the other person’s authorization.

Whether it’s a minor repair or a complete setup, the requirement is the same: both you and the other person must hold Amateur Radio Operator Certificates.

B-001-005-003, B-001-005-005, B-001-005-006

🧾 What if you have Morse and Basic qualifications?

Holding the Morse code qualification, along with your Basic certificate, extends your operating privileges in specific ways. One of these is the ability to assist with the installation of a complete amateur radio station for another licensed operator. But this privilege has limits…you can’t just set up a station for anyone.

You may perform the installation only if the other person is the holder of a valid Amateur Radio Operator Certificate. They must be legally authorized to operate the equipment once it’s installed. Without that certification on their end, even a qualified installer is not permitted to carry out the work.

B-001-005-004

🔍 B-001-005 Lesson Summary

| Concept | What It Means | Formula / Term | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Working on Another’s Equipment | Advanced operators may build or repair amateur gear for another person only if that person is authorized to use it. | Authorized Operation Rule | Ensures all equipment remains linked to a licensed holder and prevents unlicensed use. |

| Repairs and Installation | You can install or service a transmitter only when both you and the station owner hold valid certificates. | Mutual Certification Requirement | Keeps every installation within the operator’s authorized privileges and technical limits. |

| Basic and Morse Privileges | Operators with Basic plus Morse qualifications may help install a complete station for another certified amateur. | Assisted Installation | Allows cooperation among licensed hams while maintaining control by an authorized operator. |

| Unauthorized Modifications | No one may modify or convert equipment for unlicensed individuals or non-amateur use. | Regulatory Boundary | Prevents misuse of amateur gear and protects spectrum integrity. |

| Accountability | Both the helper and the station owner are responsible for ensuring lawful operation. | Shared Responsibility | Promotes cooperation while keeping compliance clear for every project or repair. |

📋 Lesson Practice Exam ▼

📘 B-001-006 –Operation of Radio Apparatus, Terms of Licence, Applicable Standards, Exempt Apparatus

Amateur radio is a licensed service governed by strict technical standards and operating rules. Whether you’re transmitting across town or tuning up a handheld VHF rig, you need to know where the legal lines are drawn. Some equipment may look flexible enough to be used across services—but staying within your authorized bands helps ensure safe, responsible, and interference-free communication.

This lesson explores who can use certain transmitters, when low-power devices need supervision, and why crossing frequency boundaries can have consequences.

🎚️ Who can operate low-power amateur transmitters?

Small transmitters, including those with power outputs of just a couple of watts, are still subject to regulation in Canada. Just because the power is low doesn’t mean the responsibilities are too. An amateur radio station with a maximum power output of 2 watts must be under the supervision of a person holding an Amateur Radio Operator Certificate and call sign.

This ensures that even very low-power operations follow proper procedures, identification rules, and don’t cause unintentional interference. Supervision is always required—even for beginners learning with simple gear.

B-001-006-001

📡 Who can you legally talk to on the air?

It’s important to know who you’re allowed to communicate with on amateur frequencies. You can’t just reach out to anyone with a radio; an amateur radio station may be used to communicate only with stations operated under similar authorizations.

That means licensed amateur operators—whether in Canada or internationally—who follow equivalent standards. Communicating with unauthorized, unlicensed, or commercial stations outside the amateur service may violate the terms of your certificate.

B-001-006-002

🔇 Can you amplify licence-exempt transmissions?

Some devices, such as certain short-range license-free transmitters (e.g., walkie-talkies, Wi-Fi devices), operate under licence exemptions. It may be tempting to boost their range using amateur gear. However, amateur radio operators are not permitted to use their equipment to enhance or extend the performance of licence-exempt transmitters. This is not permitted under any circumstances.

B-001-006-003

🚫 Can amateur equipment transmit outside amateur bands?

When is it permissible to transmit outside amateur radio bands using amateur equipment? Never, amateur radio equipment is not certified for operation outside amateur radio bands. Amateur radios are certified for use only within specific frequency bands. Even with modifications, they aren’t legally approved for transmitting on commercial, public safety, or other frequencies.

This restriction ensures safety, prevents harmful interference, and protects essential services that rely on clean, regulated spectrum use.

B-001-006-004

🛑 What are you not allowed to do with amateur radio equipment?

While amateur radio privileges are extensive, they don’t cross into other services such as use on aeronautical, marine or land mobile frequencies. These bands fall under entirely different licensing systems, each with its own technical and regulatory requirements.

Misusing amateur gear on these frequencies is both a technical and legal violation and can have enforcement consequences.

B-001-006-005

📻 When can dual-use radios be used legally?

Some VHF/UHF FM radios are capable of being programmed to operate in the land mobile service bands. This flexibility is useful, but only legal under specific conditions. If you want to use such a radio on land mobile frequencies, it must meet one key requirement: The radio is certified and licensed for use in the land mobile service.

Without this certification, using amateur gear on non-amateur frequencies—even if technically possible—is unlawful and can interfere with protected services like emergency or public works communications.

B-001-006-006

🔍 B-001-006 Lesson Summary

| Concept | What It Means | Formula / Term | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low-Power Transmitters | Any transmitter, even under 2 watts, must be supervised by a certified operator using a valid call sign. | Supervised Operation | Ensures beginners learn under control and all signals stay traceable to a licensed operator. |

| Authorized Contacts | Amateur stations may only communicate with other licensed amateur stations operating under similar authorizations. | Like-to-Like Rule | Prevents unauthorized or commercial use of amateur frequencies. |

| Licence-Exempt Devices | Amateur operators cannot boost or relay licence-exempt transmitters using amateur gear. | No Amplification Rule | Protects shared spectrum and prevents illegal signal enhancement. |

| Transmission Boundaries | Amateur radios must only transmit within the amateur bands for which they are certified. | Band Limitation | Avoids interference with public-safety, marine, and commercial services. |

| Use in Other Services | Amateur equipment may not be used on aeronautical, marine, or land-mobile frequencies. | Service Restriction | Keeps amateur privileges separate from other licensed services. |

| Dual-Use Radios | Radios that cover land-mobile bands can only be used there if they are certified and licensed for that service. | Proper Certification | Ensures compliance and prevents interference with critical communications. |

📋 Lesson Practice Exam ▼

📘 B-001-007 – Content Restrictions: Non-Superfluous, Profanity, Secret Code, Music, Non-Commercial

Amateur radio isn’t just about how we communicate—it’s also about what we’re allowed to say and share on the air. The amateur bands are not public broadcast services. They’re intended for personal, technical, and emergency use, with strict content guidelines. Certain types of communication—like business talk, music, encrypted codes, and public broadcasts—are off-limits entirely.

This lesson outlines the speech, topics, and signals that are permitted—and not permitted—under Industry Canada rules. It’s all about keeping the amateur service educational, non-commercial, and transparent.

📵 What topics and messages are strictly prohibited?

Amateur radio is not a replacement for commercial broadcasting or business communication. On-air discussions must be personal, technical, or hobby-related. Topics like Business planning are not allowed on nets or regular QSOs. In fact, In the amateur radio service, business communications are not permitted under any circumstance.

Similarly, broadcasts intended for the general public are strictly forbidden. These include pre-recorded shows, music transmissions, or anything resembling a commercial or entertainment radio service. The rules are clear: An amateur radio operator may never broadcast to the general public.

B-001-007-001, B-001-007-002, B-001-007-004, B-001-007-011

❌ What is not correct about amateur communications?

Some operators mistakenly believe that making occasional business-related comments—such as mentioning a sale or coordinating a delivery—is acceptable on the amateur bands. In reality, an amateur radio operator may conduct occasional business on the air is not allowed. Even brief references to commercial activity violate both the regulations and the non-commercial spirit of amateur radio.

Amateur radio exists for education, experimentation, and public service—not for business. Keeping the airwaves free of commercial use preserves fairness and ensures the hobby remains focused on learning and community.

B-001-007-003

🔐 Can you use secret codes, abbreviations, or encryption?

The amateur radio service is built on the principle of openness. Operators can use standard Q codes and abbreviations, but only if the meanings are widely understood. That’s why use of abbreviations if the signals or codes are not secret is permitted. Any communication that intentionally conceals meaning, even partially, goes against the purpose of amateur radio.

This same standard applies to digital modes. If you’re experimenting with new encoding techniques, you may only transmit them when it is published in the public domain. Even then, only when the encoding or cipher is not secret may a station transmit an encoded message. The expectation is that all amateur communications remain open to inspection by others in the amateur community. Above all, the transmission of a secret code by the operator of an amateur radio station is not permitted.

B-001-007-005, B-001-007-006, B-001-007-007, B-001-007-009, B-001-007-010

🎶 How do you prevent unintentional violations like retransmitting music?

Music and other non-amateur signals are not allowed on the amateur bands, even if they’re transmitted accidentally. Many violations occur when music plays in the background during a QSO—especially if a mic picks up a nearby radio or streaming device.

The simple fix…Turn down the volume of background audio. Be mindful of what your mic is capturing.

B-001-007-008

🔍 B-001-007 Lesson Summary

| Concept | What It Means | Formula / Term | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Commercial Use | Amateur radio cannot be used for business discussions, sales, or any commercial purpose. | Business Prohibition | Keeps amateur radio focused on education, experimentation, and public service, not profit. |

| Public Broadcasting | Amateur stations may not transmit to the general public or play music, news, or entertainment content. | No Broadcast Rule | Prevents the amateur bands from being used like commercial radio services. |

| False Business Activity | Even brief or casual business talk, such as advertising or product mentions, is not allowed. | Commercial Content Restriction | Protects the integrity of the hobby and avoids regulatory violations. |

| Secret Codes and Encryption | Operators may use Q codes and common abbreviations but never private or secret codes that hide meaning. | Open Communication | Ensures transparency and allows all transmissions to be monitored by the amateur community. |

| Music and External Audio | Music or other non-amateur audio cannot be transmitted, even accidentally through an open microphone. | Music Ban | Prevents copyright violations and keeps the bands clear for two-way communication. |

| Educational and Personal Focus | All amateur communication should support learning, experimentation, or personal contact between operators. | Purpose of Service | Maintains the hobby’s core values of openness, community, and non-commercial cooperation. |

📋 Lesson Practice Exam ▼

📘 B-001-008 – Installation and Operating Restrictions: Number of Stations, Repeaters, Home-Built, Club Stations

Operating a station in Canada comes with technical privileges—but also specific qualifications for certain types of installations. Whether you’re running a simple home rig, setting up a repeater, or helping install a club station, your level of certification determines what you’re legally allowed to do.

This section focuses on who can build, install, or operate different types of amateur stations—including cross-band repeaters, remote transmitters, and non-commercial RF amplifiers. Knowing your limitations is part of operating responsibly.

📍 Where can you operate in Canada—and what about one-way signals?

Holders of a valid certificate aren’t limited by province or region. In fact, authorized amateurs may legally operate Anywhere in Canada. Whether you’re on a backcountry camping trip in BC or at a cottage in Nova Scotia, your callsign and privileges go with you.

However, not every kind of transmission is allowed in every context. One-way communications, for instance, are typically restricted—but there’s one exception. A Beacon station may transmit one-way communications for propagation testing and similar functions.

B-001-008-001, B-001-008-002

🧰 Can anyone assemble or install amateur gear?

Assembling gear isn’t the same as building from scratch. To legally put together professionally designed transmitter kits, an operator must hold at least the Basic qualification. This ensures the operator understands safety, component handling, and legal limitations.

But for more advanced installations—such as setting up a repeater, club station, or working with non-commercial gear—more knowledge is required. In these cases, operators must hold Basic and Advanced certification. These tasks involve higher technical responsibility and potential for broader RF exposure or interference, so the elevated qualification makes sense.

B-001-008-003, B-001-008-004, B-001-008-005, B-001-008-006

🔁 Can you operate a cross-band repeater or remote transmitter?

Cross-band repeaters are an important tool in amateur radio, allowing signals to be relayed across bands for greater coverage. These setups are relatively straightforward and require only a Basic qualification to operate. That means most hams can explore this feature as soon as they’re licensed.

However, controlling a transmitter remotely including adjusting frequency, output power, or emission mode is a more advanced procedure. The operator must hold Basic and Advanced qualifications to comply with the regulations,.

B-001-008-007, B-001-008-008

🔍 B-001-008 Lesson Summary

| Concept | What It Means | Formula / Term | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nationwide Operation | Licensed amateurs may operate anywhere in Canada; callsigns and privileges are valid nationwide. | Portable Privilege | Provides freedom to operate while travelling without additional licensing. |

| One-Way Signals | One-way transmissions are not permitted except for beacon stations used in propagation testing. | Beacon Exception | Allows limited one-way signals for research while avoiding unauthorized broadcasting. |

| Building or Assembling Gear | Operators with a Basic qualification may assemble or use transmitter kits designed for amateur use. | Basic Kit Assembly | Encourages learning and safe building practices within licensed limits. |

| Advanced Installations | Installing repeaters, club stations, or experimental transmitters requires both Basic and Advanced certificates. | Advanced Installation | Ensures technically complex or high-power systems are handled by qualified operators. |

| Cross-Band Repeaters | Cross-band repeater operation is permitted with a Basic qualification. | Basic Repeater Privilege | Gives new operators experience in relaying signals responsibly within amateur bands. |

| Remote Transmitter Control | Changing frequency, power, or mode remotely requires both Basic and Advanced qualifications. | Remote Operation Rule | Prevents misuse of remotely controlled stations and ensures accountability. |

📋 Lesson Practice Exam ▼

📘 B-001-009 – Participation in Communications by Visitors, Use of Station by Others

Operating your amateur radio station isn’t just about what you do—it’s about who else uses your equipment, how they’re supervised, and what your responsibilities are when guests or family members get on the mic. The control operator has legal responsibility while transmitting, and the station owner shares that responsibility in ensuring the station complies with regulations.

This section outlines who may operate, under what conditions, and how to stay compliant when others use your radio gear—whether they’re licensed or not.

👥 Who’s responsible for the station’s operation?

Running a station isn’t a solo responsibility. Legally, Both the control operator and the station owner are responsible for how the station is operated. That’s true whether you’re using your own station or someone else’s.

If you transmit from another station, it’s not just the owner’s responsibility. In that case, Both of you are jointly responsible. And if you own a station, You are responsible for the operation of the station in accordance with the regulations—even if someone else is using the gear under your permission.

B-001-009-001, B-001-009-002, B-001-009-003

🎙️ Who can be a control operator—and when are they required?

You can’t just let anyone operate your station unsupervised. The control operator must be Any qualified amateur radio operator chosen by the station owner. Whether it’s a club net, public demonstration, or just casual operation, someone qualified must be in control at all times.

A control operator must be present? Whenever the station is transmitting. That control operator must also be physically located At the station’s control point. There’s no “autopilot” mode in amateur radio—if it’s on the air, someone qualified must be in control.

B-001-009-004, B-001-009-005, B-001-009-006

👪 Can your friends or family use your station?

Friends or family members who are not licensed may only operate your station if you are right there supervising them. You must remain present and in control of the station at all times, and the responsibility for every transmission rests with you as the certificate holder.

The rules state clearly: They must hold suitable amateur radio qualifications before they are allowed to be control operators. If they aren’t licensed, they can still transmit—but only if When the person is under supervision, and in the presence of, a person holding appropriate qualifications. In short, unlicensed operators can only go on-air while directly observed by a certified amateur.

B-001-009-007, B-001-009-009

🆗 What can the station owner authorize?

As the station owner, you’re allowed to let others use your radio—but only under proper conditions. You may permit any person to operate the station under the supervision and in the presence of the holder of an Amateur Radio Operator Certificate. That means you’re responsible for ensuring they’re watched closely and that no violations occur on your watch.

Being a responsible station owner involves knowing these rules and following them anytime you invite someone to use your gear—whether they’re a curious friend or a new ham getting on the air for the first time.

B-001-009-008

🔍 B-001-009 Lesson Summary

| Concept | What It Means | Formula / Term | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shared Responsibility | Both the control operator and the station owner are legally responsible for proper station operation. | Joint Accountability | Clarifies that neither party can avoid responsibility for illegal or improper transmissions. |

| Control Operator Requirement | Every transmitting station must have a qualified control operator chosen by the station owner. | Qualified Control | Ensures that a certified person is always in charge whenever the transmitter is active. |

| Control Point Presence | The control operator must be physically present at the control point whenever the station is on the air. | Active Supervision | Prevents unattended operation and maintains immediate control over all transmissions. |

| Unlicensed Guests | Friends or family may operate only when directly supervised by a licensed amateur who is present. | Supervised Operation | Allows demonstrations and training while keeping responsibility with the licensed operator. |

| Owner Authorization | A station owner may allow others to use the station only under supervision by a qualified certificate holder. | Permission Rule | Ensures proper oversight and compliance whenever guests or club members use shared equipment. |

📋 Lesson Practice Exam ▼

📘 B-001-010 – Interference, Determination, Protection from Interference

In amateur radio, managing interference is a matter of both technical skill and regulatory responsibility. Knowing what causes interference, how it’s classified, and when to stop transmitting are essential parts of operating legally. Whether you’re sharing a band with primary users or testing a new setup, it’s your duty to avoid causing problems for others.

This lesson will help you understand the definitions and rules around interference, how band-sharing works, and what authority Industry Canada has to protect the airwaves.

📡 What is harmful interference—and when is it never allowed?

Any time your transmission affects another service’s ability to operate normally, it’s considered interference. When that interference is especially disruptive or persistent, it’s classified as Harmful interference. This includes blocking, degrading, or repeatedly interrupting communication signals.

There is zero tolerance for intentional interference on the amateur bands. Deliberate interference is never acceptable. No matter the reason or personal dispute, malicious jamming or intentional QRM violates regulations and could lead to fines and suspension.

B-001-010-001, B-001-010-002, B-001-010-005

🔄 Who gets priority—and what if multiple hams want the same frequency?

Amateur radio operators are allowed to use the frequency band only if they do not cause interference to primary users if amateur radio is listed as a “secondary user” of a frequency band. For example, hams often share bands with government, public safety, or commercial systems that always have priority.

When two amateurs want to use the same frequency they are required to work out the conflict cooperatively, as Both station operators have an equal right to operate on the frequency. That means—not by overpowering or jamming the other signal.

B-001-010-003, B-001-010-004

⚖️ What can the Minister do about interference?

If a station causes harmful interference, the Minister of Innovation, Science and Industry has the legal authority to intervene. This is taken seriously—especially if a station interferes with emergency or commercial communications.

In such cases, the Minister may Order the station’s operation to cease or change. This could include temporary shutdowns, frequency changes, or full suspension of operating privileges until the issue is resolved.

B-001-010-006

📶 Which bands require extra caution—and when are hams unprotected?

Some amateur bands are also shared with powerful or license-exempt devices, like industrial controllers and consumer electronics. In the 70 cm band, hams must avoid interfering with primary users operating in the 430.0 MHz to 450.0 MHz range. This means operating with care near sensitive services like military or public safety systems.

Conversely, amateur radio operations are not protected from interference in some ranges, including 902 MHz to 928 MHz. Unlicensed devices like cordless phones, baby monitors, and IoT equipment (physical objects that are connected to the internet and can collect, send, or receive data) may flood these bands, and hams have no legal protection from that interference.

B-001-010-007, B-001-010-008, B-001-010-010

🧪 When is it safe to conduct test transmissions?

Test transmissions are a routine part of station setup, tuning, and experimentation. However, operators must ensure that tests do not interfere with other users. You may only proceed When the transmission will not cause interference to stations in the amateur radio service or other services.

This includes checking SWR, adjusting power levels, or experimenting with modes. Always listen first and confirm the frequency is clear.

B-001-010-009

🔍 B-001-010 Lesson Summary

| Concept | What It Means | Formula / Term | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Harmful Interference | Any signal that blocks, degrades, or disrupts another service is harmful interference and never allowed. | Zero-Tolerance Rule | Protects all radio users and maintains the integrity of shared spectrum. |

| Frequency Priority | Amateurs must avoid interfering with primary users and share frequencies courteously with other hams. | Secondary-User Rule | Ensures cooperation and respect when bands are shared with government or commercial systems. |

| Ministerial Authority | The Minister of Innovation, Science and Industry can order a station to change or stop transmitting if it causes interference. | Cease-or-Change Order | Provides legal enforcement to protect critical services and emergency communications. |

| Shared and Unprotected Bands | Amateurs must use care in 430–450 MHz (shared) and have no protection in 902–928 MHz against interference from devices. | Band Caution Zones | Reminds operators that some frequencies carry extra risk of interference and limited protection. |

| Test Transmissions | Testing and tuning are allowed only when they will not cause interference to any station or service. | Check-Before-Transmit | Promotes good operating habits and prevents unintentional disruption while experimenting. |

📋 Lesson Practice Exam ▼

B-001-011 – Emergency Communications (Real or Simulated), Communication with Non-Amateur Stations

When disaster strikes, amateur radio operators often play a vital role. In emergency situations—whether real, simulated, or civil support—operators often help maintain communication between agencies, communities, and responders. That responsibility comes with clear rules and special permissions. It’s also a time when some normal restrictions are lifted to allow fast, effective response.

This section explores how amateur radio fits into emergency operations, including power limits, message handling, and when it’s legal to ‘bend’ the rules to save lives or assist with the communications component of disaster relief.

🆘 What can hams do in a distress or emergency situation?

During a real emergency, operators are permitted to use whatever tools are needed to get the message through. That includes using any frequency within amateur bands—even if you’re not normally authorized for it—if you hear a distress call. In such a case, you may respond and offer assistance.

An operator in distress may use any means of radiocommunication within the amateur bands to call for help. That means there’s No limitations on transmitter power, frequency privileges, or modes when life or safety is at stake. You may even interfere with another transmission—but only When your station is directly involved with a distress situation.

B-001-011-003, B-001-011-005, B-001-011-007, B-001-011-010

📡 Who can you communicate with—and when is broadcasting allowed?

Under normal conditions, amateur operators may engage in communications only with other amateur radio stations. Contact with commercial, government, or public service users is not allowed unless it occurs under officially recognized emergency protocols. Even in a disaster, operators must stay within the rules: using frequencies outside amateur radio bands is never permitted. All transmissions must take place on authorized amateur frequencies, regardless of the circumstances.

There is one exception to standard procedures during emergencies. If life or property is at immediate risk, radio communications required for the safety of life and property may be sent without concern for format or structure. This means you can abandon formal procedures and send clear, plain-language messages to get help fast. However, this does not extend to frequency use…you must still operate within your licensed amateur bands and follow all technical limits.

B-001-011-001, B-001-011-002, B-001-011-004

🛰️ When are special emergency permissions activated?

Hams may be called upon when commercial systems break down. During disasters or crises, amateur stations are permitted to transmit essential messages—but only When normal communication systems are overloaded, damaged or disrupted. This is the legal trigger for emergency amateur traffic.

During such times, operators can handle messages from public safety agencies, but only under structured arrangements. That includes During peace time, civil emergencies and exercises when practicing or assisting.

While amateur operators can send messages related to the safety of life and property during emergencies (see Section 48 of the Radiocommunication Regulations), they must still operate within the frequency bands authorized for their specific qualifications.

This means:

- A Basic-only operator without HF privileges is not legally permitted to transmit on HF, even during emergencies.

- Doing so would still be considered unauthorized operation under Canadian law.

✅ What you Can Do:

- Operate on VHF/UHF bands where you are licensed

- Relay emergency messages through repeaters or local nets

- Assist a licensed operator who has HF privileges, if present

B-001-011-006, B-001-011-009

🛑 What’s expected from operators not part of the emergency net?

One of the most helpful things an operator can do during a crisis is to give space. If you are not officially involved in an emergency net, your job is simple: Avoid needless transmissions on or near the net frequency. That includes tuning up, testing, or chatting nearby, all of which can block or degrade emergency communications.

Silence, in this case, is a form of participation. Listen first—and don’t transmit unless you’re part of the net or offering legitimate assistance.

B-001-011-008

📡 Emergency Operations Matrix – Canada

| Situation | Basic Only (<80%) | Basic with HF (≥80%) | Advanced | Unlicensed Person |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transmit on HF (Below 30 MHz) | ❌ Not allowed – even in emergency | ✅ Allowed within HF band limits | ✅ Allowed | ❌ Never allowed |

| Transmit on VHF/UHF (Above 30 MHz) | ✅ Allowed | ✅ Allowed | ✅ Allowed | ❌ Only under direct supervision |

| Use of modes not normally used (e.g., CW, digital, SSB) | ✅ If within authorized bands | ✅ If within authorized bands | ✅ If within authorized bands | ❌ |

| Maximum transmit power | ❌ Limited to 560 W PEP max | ❌ Limited to 560 W PEP max | ✅ May exceed 560 W PEP in emergency | ❌ |

| Contact non-amateur stations (e.g., police, marine, commercial) | ❌ Not allowed | ❌ Not allowed | ❌ Not allowed | ❌ |

| Use non-amateur bands (e.g., marine, land mobile) | ❌ Never permitted | ❌ Never permitted | ❌ Never permitted | ❌ |

| Respond with unusual message format / plain language | ✅ Yes, if life/property at risk | ✅ Yes | ✅ Yes | ❌ Only under supervision if licensed |

| Transmit emergency traffic (life/property) | ✅ Within VHF/UHF bands only | ✅ On all licensed bands | ✅ On all licensed bands | ❌ Unless under direct control |

| Participate in emergency drills/exercises | ✅ Within licensed privileges | ✅ Within licensed privileges | ✅ Within licensed privileges | ❌ Unless supervised |

🔍 B-001-011 Lesson Summary

| Concept | What It Means | Formula / Term | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emergency Privileges | In real distress, operators may use any amateur frequency or power to send calls for help. | Distress Exemption | Allows lifesaving messages without concern for normal limits or interference. |

| Authorized Contacts | Normally, communication is limited to other amateur stations; non-amateur contacts are forbidden except in recognized emergencies. | Communication Scope | Keeps amateur activity within licensed services and prevents cross-service interference. |

| Emergency Activation | Special permissions apply only when normal systems are overloaded, damaged, or disrupted. | Disaster Trigger | Defines when hams may handle official or public-safety messages during crises. |

| Operator Limits | Each operator must stay within their certified frequency bands, even in emergencies. | Privilege Boundaries | Reinforces that emergency help never overrides licensing restrictions. |

| Non-Net Operators | Operators not involved in emergency nets must remain silent near net frequencies. | Silence Protocol | Prevents congestion and keeps channels clear for priority traffic. |

📋 Lesson Practice Exam ▼

📘 B-001-012 – Non-Remuneration, Privacy of Communications

Amateur radio is built on the principles of public service, shared learning, and mutual respect. That means the hobby is not to be used for personal profit or commercial gain. Likewise, operators are expected to uphold a high standard of privacy and integrity when it comes to the content they hear on the air.

In this section, you’ll learn about the rules surrounding compensation, message privacy, and when you’re allowed—or not allowed—to share the content of amateur transmissions.

💸 Can you get paid to relay messages or operate on the air?

The amateur bands are strictly non-commercial. Operators are not permitted to accept compensation for any activity that involves sending, receiving, or handling messages—even if it’s a favor or a third-party relay. That’s why No payment of any kind is allowed for third-party messages sent by amateur stations.

So, when is it ok to get paid?Never, it is expressly prohibited to demand or accept payment for exchanging messages. Whether it’s an emergency relay, a net check-in, or a DX report, your time on the air is always volunteer-based.

B-001-012-001, B-001-012-003

🔒 When can you share what you hear on the air?

Amateur radio operates on open frequencies, but that doesn’t mean everything you hear can be repeated. Operators must use discretion when discussing on-air content. You may only share what you hear if it was transmitted by an amateur radio station. This is because amateur radio is a public, non-confidential service, where exchanges between licensed amateurs are considered open communications by design.

However, there are clear legal limits. It becomes an offence to disclose private or non-broadcast transmissions when it is for the purpose of answering questions from a media organization. Even if a journalist asks about what was said on the air, you cannot share the content unless it was broadcast or officially authorized. Practicing discretion protects operators, preserves trust, and upholds the integrity of the amateur service.

B-001-012-002, B-001-012-004

🔍 B-001-012 Lesson Summary

| Concept | What It Means | Formula / Term | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Commercial Operation | Amateur radio is strictly voluntary and may not be used for paid work or business gain. | Volunteer-Only Rule | Keeps the service focused on learning, experimentation, and community—not profit. |

| Payment for Messages | Operators cannot demand or accept money or reward for sending or relaying any message. | No-Compensation Policy | Maintains fairness and prevents the hobby from becoming a commercial service. |

| Sharing On-Air Content | You may discuss or repeat only what was transmitted by amateur stations in open communication. | Open-Frequency Standard | Respects the public nature of amateur exchanges while protecting personal privacy. |

| Media Disclosure | It is an offence to share private or non-broadcast transmissions for news or media purposes. | Privacy Regulation | Protects trust between operators and prevents misuse of information heard on the air. |

| Ethical Conduct | Operators are expected to act with honesty, respect, and discretion in all communications. | Operator Integrity | Upholds the reputation of amateur radio as a respectful, community-driven service. |

📋 Lesson Practice Exam ▼

📘 B-001-013 – Station Identification, Call Signs, Prefixes

Every amateur radio station must be clearly identified on the air. Your call sign is your legal signature and primary way to signal who you are, where you’re transmitting from, and that you’re operating within the rules. Canada has specific regulations about when, how, and in what language you identify your station.

This lesson covers the essential points about call signs, transmission intervals, and station identification rules—including how often to identify, which prefixes are Canadian, and the one exception when identification is not required.

🧾 What is a valid Canadian amateur call sign—and when must it be used?

A call sign not only identifies you legally, but it must also follow format conventions. In Canada, valid call signs typically begin with VA, VE, VO or VY. A good example would be VA3RAC, which follows both prefix and region assignment guidelines.

You must announce your call sign at the beginning and at the end of each contact, and repeat it at least every thirty minutes during longer exchanges. This timing ensures that anyone listening can confirm who is transmitting. The rules are the same for a test or a radio contact.

B-001-013-001, B-001-013-002, B-001-013-003, B-001-013-010, B-001-013-011

🗣️ When are call signs required during QSOs?

When two amateurs begin a QSO, Each station must transmit its own call sign. This confirms each operator’s identity before communications proceed. The same rule applies at the end of a contact: Each station must transmit its own call sign again to properly close the exchange.

Additionally, no station may transmit for longer than 30 minutes without identifying. This helps ensure ongoing accountability, especially during long nets or contests.

B-001-013-004, B-001-013-005, B-001-013-006

🔊 Are there any exceptions to identifying?

There is only one scenario in which you may transmit without identifying your station: Only to control a model craft. This exemption allows for control signals to be sent without repeatedly stating the call sign, which would be impractical for rapid telemetry or directional control.

For all other transmissions—including brief tests, pings, or tuning—you must still identify As The rules are the same for a test or a radio contact.

B-001-013-007, B-001-013-010

🌐 What language must be used when identifying?

When transmitting your call sign, you must use either of Canada’s two official languages. Identification is legal only in English or French. Using phonetics, abbreviations, or non-standard language doesn’t replace the requirement to use recognized, clearly spoken language when announcing your call sign.

This helps all listeners understand who is transmitting and ensures your signal is clearly traceable.

B-001-013-008

🔍 B-001-013 Lesson Summary

| Concept | What It Means | Formula / Term | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Canadian Call Sign Format | Valid call signs begin with VA, VE, VO or VY and identify the operator’s region and licence. | Canadian Prefixes | Creates a unique national identity and ensures traceability of every signal on the air. |

| Identification Timing | State your call sign at the start and end of each contact, and at least once every 30 minutes. | 30-Minute Rule | Provides clear accountability and helps others confirm who is transmitting. |

| Call Signs in QSOs | Each station must transmit its own call sign at both the beginning and end of a QSO. | Identification Cycle | Keeps exchanges organized and avoids confusion during multi-station activity. |

| Identification Exception | Identification is not required only when sending control signals to model craft. | Model Control Exemption | Allows short, rapid control transmissions without repeating call signs unnecessarily. |

| Language Requirement | Call signs must be spoken in either English or French using clear, standard pronunciation. | Official Languages Rule | Ensures identification is understandable nationwide and by international listeners. |

📋 Lesson Practice Exam ▼

📘 B-001-014 – Foreign Amateur Operation in Canada, Banned Countries, Third-Party Messages

International communication is one of the most rewarding aspects of amateur radio. But when operators cross borders—whether physically or over the airwaves—specific rules apply. Canada has agreements in place with many countries to allow visiting operators limited use of the airwaves, while also protecting the integrity of domestic operations. Equally important are the rules around third-party messages and which countries can or cannot participate in message exchanges.

This lesson covers what happens when foreign operators transmit in Canada, how third-party messages are handled, and which protocols are in place for global emergencies and disasters. It also explains when and how a Canadian amateur can legally communicate on behalf of someone else.

🛰️ Who can operate in Canada—and under what conditions?

The CEPT Agreement (Recommendation T/R 61-01) enables amateur radio operators from participating countries to operate in each other’s territories without obtaining additional licenses, provided they hold the appropriate qualifications. In Canada, this agreement is recognized by Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada (ISED), allowing visiting European amateurs with CEPT licenses to operate with Advanced privileges. Conversely, Canadian amateurs with both Basic and Advanced qualifications can apply for a CEPT permit through Radio Amateurs of Canada (RAC) to operate in CEPT member countries.

Therefore, foreign amateur radio operators may transmit from Canadian soil, but only if Their country has an agreement with Canada and the amateur radio operator has obtained the appropriate permit. The CEPT agreement is one such path, allowing European hams to transmit with Advanced privileges while visiting Canada, as authorized by Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada.

If a U.S. operator is on air in Canada, they must properly identify themselves. This includes stating Location by city and province at least once per contact, and, when using voice, also giving The Canadian call sign prefix for the geographic location of the station. These identifiers ensure that transmissions are legal and traceable within the Canadian regulatory framework.

B-001-014-002, B-001-014-005, B-001-014-009, B-001-014-010

📨 What about third-party communications?

Canada permits third-party message handling under specific circumstances. Operators may send a message on behalf of another person because Canada does not prohibit international communications on behalf of third parties. However,Only communications of a personal and non-commercial nature are allowed.

Even in emergencies, certain limits apply. International third-party communications during disasters are generally allowed, except when specifically prohibited by the foreign administration concerned. For example, if the destination country has opted out through the ITU, those communications must not occur. In some cases, The country has filed an objection to such communications with the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) restricting third-party communications.

B-001-014-003, B-001-014-004, B-001-014-006, B-001-014-007

🧑🤝🧑 Who is a third party—and what happens in shared transmissions?

It’s important to know who qualifies as a third party. For example, if Both non-certified persons (such as a Canadian friend and a visiting operator’s friend) are engaged in communication using your station, both are considered third parties—and communication is not permitted unless regulations allow it.

If your certified friend is operating your station and a foreign station breaks in to address the unlicensed party, your job is to Continue monitoring the communications of your friend. You cannot allow unlicensed persons to handle transmissions independently.

Canadian stations can exchange third-party messages with any other amateur radio station—but only within the boundaries of the regulations already discussed.

B-001-014-001, B-001-014-008, B-001-014-011

🔍 B-001-014 Lesson Summary

| Concept | What It Means | Formula / Term | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reciprocal Operating Privileges | Foreign amateurs may operate in Canada only if their country has a formal agreement or CEPT recognition with ISED. | CEPT T/R 61-01 Agreement | Allows qualified visitors to operate temporarily while maintaining full traceability and legal compliance. |

| Canadian Prefix Use | Visiting operators must identify with both their call sign and the Canadian prefix for the province of operation. | Call Sign Identification Rule | Shows location clearly and ensures transmissions meet Canadian identification standards. |

| Canadian CEPT Privilege | Canadian operators with Basic + Advanced qualifications may obtain a CEPT permit through RAC to operate abroad. | Reciprocal Permit | Provides international access while maintaining regulatory parity among CEPT nations. |

| Third-Party Message Policy | Canada allows third-party messages if they are personal, non-commercial, and the other country does not prohibit them. | Non-Commercial Traffic | Supports international goodwill while respecting ITU and national restrictions. |

| Prohibited Countries | Third-party communication is banned with nations that have filed ITU objections to such traffic. | ITU Objection List | Prevents illegal or unauthorized message exchange with restricted jurisdictions. |

| Definition of Third Party | A non-licensed person communicating through an amateur station counts as a third party and must follow all regulatory limits. | Third-Party Definition | Clarifies who can speak on the air and under what supervision to maintain control and accountability. |

📋 Lesson Practice Exam ▼

📘 B-001-015 – Frequency Bands and Qualification Requirements

In amateur radio, knowing which bands you can operate on—and under what qualifications—is essential for both compliance and effective operation. Frequency privileges in Canada are linked directly to the certification level you hold, and extra rules apply for operating below 30 MHz. Additionally, frequency ranges for specific HF bands must be memorized, especially for exam readiness and on-air operation.

This lesson will help you understand the link between exam performance and band access, the limits of control operator authority, and the specific band allocations across popular HF bands. You’ll also learn where you’re permitted to control model craft under Canadian regulations.

🪪 Operating Privileges and Certification

In amateur radio, it doesn’t matter who controls your equipment—it matters who holds the qualifications. If someone with more advanced certification operates your station using your callsign they’re still limited to only the privileges allowed by your qualifications. This ensures that certification levels are respected regardless of who is in control.

The same is true in reverse: if you are operating another person’s station and they have higher qualifications than you, you are still limited to Only the privileges allowed by your qualifications. The system is designed to keep operations consistent with the certification of the control operator, not the owner of the equipment.

B-001-015-001, B-001-015-002

📉 Accessing Bands Below 30 MHz

The lower-frequency amateur bands—below 30 MHz—are part of the coveted HF spectrum, and not everyone gets automatic access. Even after passing the Basic written examination, you must do more. Specifically, You must attain a mark of 80% on the Basic examination, or pass an Advanced or Morse code examination. These rules ensure operators on these bands have a higher level of training or experience.

Canadian amateurs who meet this standard can then operate across a wide range of bands, including some of the most popular international HF bands like 40 metres, 20 metres, and 10 metres.

B-001-015-003

🎮 Radio-Controlled Models

The operation of model aircraft, boats, or cars using amateur radio frequencies is strictly controlled. The rule is simple and straightforward: a licensed amateur may only use bands on all amateur radio bands above 30 MHz for this purpose. This ensures that model control operations stay within predictable, interference-safe regions of the spectrum.

This same frequency limit applies when determining which spectrum portions can legally support remote-control signals without overlapping with critical HF communication channels.

B-001-015-004, B-001-015-011

📡 Canadian HF Band Ranges

You’ll need to memorize the official frequency ranges of the major HF bands in Canada. Here’s a breakdown of the most common allocations:

- 160-metre band: 1.8 MHz to 2.0 MHz

- 80-metre band: 3.5 MHz to 4.0 MHz

- 40-metre band: 7. 0 MHz to 7.3 MHz

- 20-metre band: 14. 000 MHz to 14.350 MHz

- 15-metre band: 21.000 MHz to 21.450 MHz

- 10-metre band: 28.000 MHz to 29.700 MHz

These band edges are based on national regulations and international agreements and this knowledge is tested frequently in Basic Qualification exams.

B-001-015-005 to B-001-015-010

🔍 B-001-015 Lesson Summary

| Concept | What It Means | Formula / Term | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operator Privilege Rule | Each operator may use only the privileges that match their own certification level, regardless of whose equipment is used. | Certification Control | Keeps operations consistent and ensures responsibility lies with the qualified control operator. |

| HF Band Access | To operate below 30 MHz, you must score at least 80% on the Basic exam or hold Advanced or Morse qualifications. | 80% Rule | Ensures HF operators have the skill and knowledge needed for complex communications. |

| Model Craft Operation | Radio-controlled models may be operated only on amateur bands above 30 MHz. | 30 MHz Limit | Keeps model control away from HF bands and prevents interference with long-distance communication. |

| Canadian HF Bands |

160 m – 1.8 to 2.0 MHz 80 m – 3.5 to 4.0 MHz 40 m – 7.0 to 7.3 MHz 20 m – 14.000 to 14.350 MHz 15 m – 21.000 to 21.450 MHz 10 m – 28.000 to 29.700 MHz |

HF Band Allocations | Defines key operating ranges for Canadian amateurs and forms part of Basic exam knowledge. |

| Qualification and Control | Privileges follow the control operator’s certification, not the equipment owner’s licence. | Control Operator Principle | Ensures consistent enforcement and prevents unqualified operation across stations. |

📋 Lesson Practice Exam ▼

📘 B-001-016 – Maximum Bandwidth by Frequency Bands

📡 Understanding Bandwidth Limits

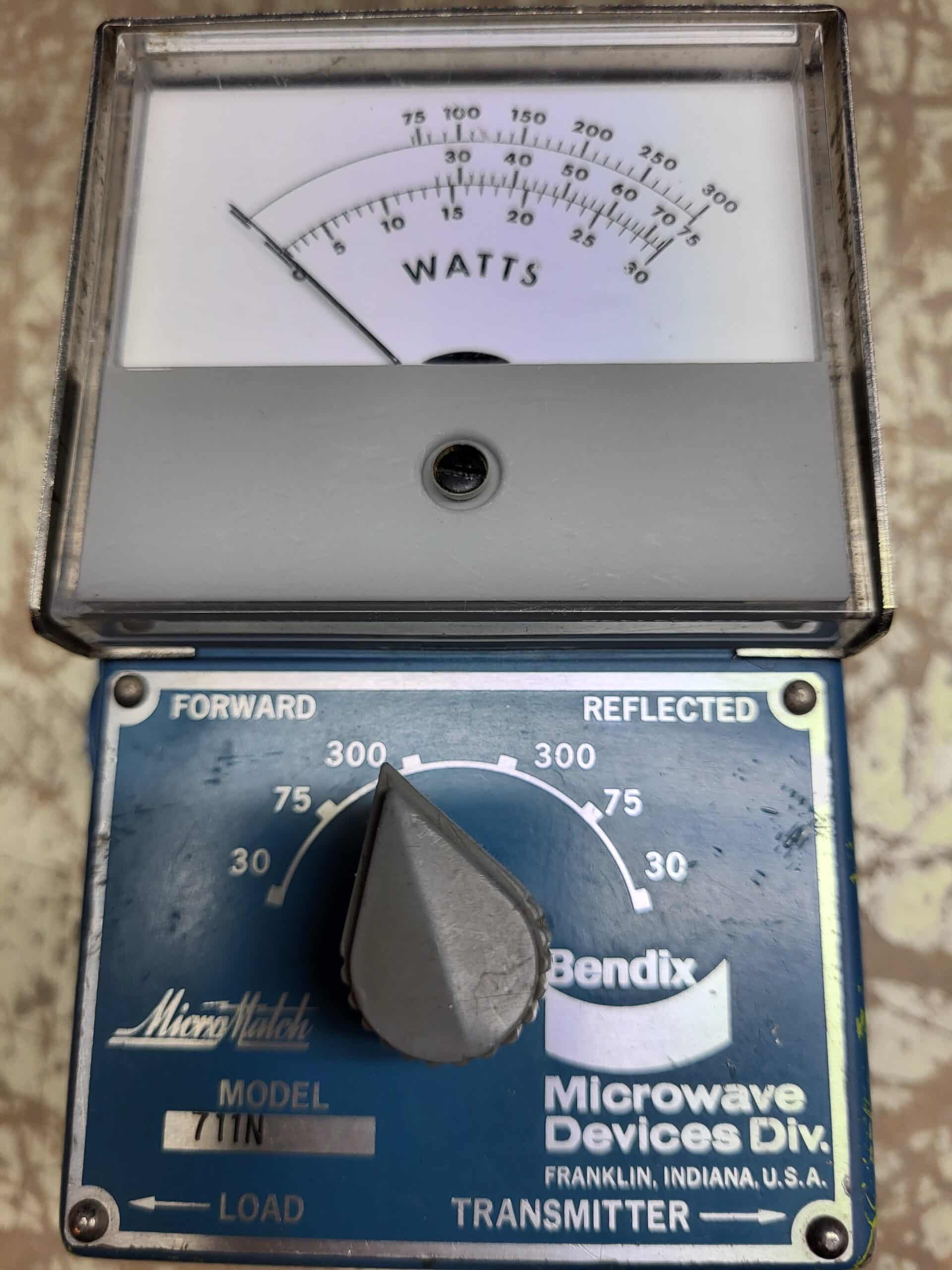

Bandwidth refers to the range of frequencies a radio signal occupies. In amateur radio, every transmission has a certain width depending on the mode and modulation being used—voice signals, for instance, use more bandwidth than Morse code. To avoid interference and ensure fair use of the radio spectrum, there are regulatory limits on the bandwidth of signals in specific frequency bands.

Understanding bandwidth restrictions is essential for operating legally and responsibly as a Canadian amateur radio operator. These rules not only maintain orderly use of the spectrum but also prevent one operator from unintentionally (or intentionally) interfering with another. Each amateur band has specific limits set out by Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada (ISED), and exceeding these could result in unwanted interference or even penalties.

⚙️ Standard Limits Across the Bands

On some bands operators have more room to work with. For instance, the maximum authorized bandwidth on the 2-metre bands is 30 kHz, which accommodates FM voice transmissions and other wideband modes. The same bandwidth limit applies to the 50–54 MHz range, where 30 kHz is also allowed. These wider bandwidths make these bands suitable for high-fidelity voice or even digital operations.

On HF, however, the restrictions are tighter to conserve space for more operators. In the 28–29.7 MHz portion of the 10-metre band, the maximum transmission bandwidth drops to 20 kHz. Even more restrictive are bands between 7 MHz and 25 MHz—except for one special exception—where the maximum bandwidth is 6 kHz. These narrow limits are in place to prevent congestion and overlap between different stations and modes.

B-001-016-001 to B-001-016-005

🚫 Where Certain Modes Are Not Allowed